Coaching legends prepare to share their wisdom in Winnipeg

The National Coaches’ Conference in Winnipeg May 27 to 30 for both coaches and officials will offer a hint of just how Canadians are taking the lead in all pressing questions relating to skating.

Held as part of Skate Canada’s Annual Convention General Meeting (ACGM), this year’s theme “Partners in Progress” promises to offer an excellent range of workshops and social networking opportunities to the participants – Skate Canada coaches, officials, and international coaches as well. As a result of Skate Canada changing their bylaws, NCCP certified Skate Canada coaches will become full voting members of the association for the very first time, which marks the importance of the voice of coaches.

“Skate Canada is really working on the coaching and I think that is so key,” says Tracy Wilson, slated to give two skating skills workshops at the conference. “It’s such a resource and we share information because we all have our fields of expertise and when we come together and share, we all benefit.”

Skate Canada has identified partnerships as the glue that binds together all of their strategic imperatives to 2018. One of those partnerships is with Hockey Canada to bring the joy of skating to all Canadians. Guest speaker at the NCC opening dinner is Melody (call her Mel) Davidson, coach of the women’s hockey team that won gold at the 2006 and 2010 Olympics. She’s a builder of her sport, which now emphasizes speed and skill so much.

Speaking of partnerships, the 2015 ACGM/NCC will also feature Kaitlyn Weaver and Andrew Poje and Olympic women’s hockey team gold medalist Meaghan Mikkelson, who also teamed up with hockey colleague Natalie Spooner to win seven legs of The Amazing Race Canada during the show’s second season.

Yes, a big field is opening up to skating, with its well organized skills system, especially with the new CanSkate program, which teaches learn-to-skate skills to youngsters who may become speed skaters or hockey players, or ringette players or adults who skate for the love of it.

At the conference, Wilson will go through many of the exercises she has used and developed over the years, starting with her work as an Olympic medalist in ice dancing with Rob McCall, her work with hockey players, and finally with international skaters such as Olympic champions Xue Shen and Hongbo Zhao, Yu Na Kim, and Yuzuru Hanyu and European champ Javier Fernandez. She and coach Brian Orser have both “honed in on what works to help different skaters,” she said. Her first workshop will show basic skills and exercises (“It’s everything that everybody knows but with a different slant,” she says) and the next class is about how to develop them.

The conference is packed with other gems: renowned Winnipeg sports psychologist Dr. Cal Botterill will speak about how to prevent burnout and “under-recovery” in athletes and coaches; sport headliners Sally Rehorick, Dr. Jane Moran and Monica Lockie will probe the burning problem of troublesome boots and blades; and judge Karen Howard will expound on what the referee says to the panel before an event (information coaches don’t want to miss!). Dr. William Bridel offers up chats about currently hot topics of bullying in sport and pain and injury from a socio-cultural perspective; Donna King and Lockie will preview the next chapter of the CanSkate juggernaut with new materials, resources and activities; and choreographer Mark Pillay will present on-and-off-ice workshops on musicality (and as an extra treat, his pupil Liam Firus will show off his new programs for 2015-2016.).

Rehorick and friends have already been busy behind the scenes conducting an informal six-month investigation into the effects of boot and blade selection on the performance of skaters at all levels and will try to propose the next steps toward research and education.

Rehorick has spoken with coaches, doctors, parents, researchers, skate technicians, distributors, team leaders and administrators about the problem. Sadly, she’s seen skaters at the Learn-to-Train and Learn-to-Compete levels struggling with boots that “seemed to control the skater, rather than the other way around.” The problem is a world-wide one. The ISU has been studying it through medical commission chair Dr. Moran, a Canadian.

Dr. Bridel, a former Skate Canada employee and now a professor at the University of Calgary’s department of kinesiology, will discuss preventive measures with bullying issues, rather than reactive strategies and how kids are exposed to bullying in the larger sociocultural context. He sees bullying becoming more of a problem because of social media. He’s also involved with a bystander intervention group at the university.

He also describes a culture that prevents skaters from revealing an injury, so that they don’t get help when they need it. Again, prevention is the key.

Dr. Botterill’s chat will be vital. “Under-recovery is kind of like an epidemic,” he says. “In high performance fields, people are pushing the envelope so hard, life in this era has so many distractions, and people aren’t recovering in the way they need to.”

Over the past 15 years of his 40-year career, most of Dr. Botterill’s work has been focused on helping people get rest and regain their health – and performance levels. Technology is addictive, he warns. He believes a high percentage of people are burned out and don’t even know it.

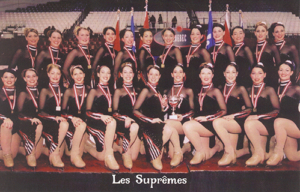

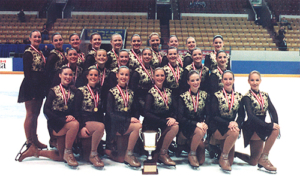

Last year, the National Coaches’ Conference reached a height of 275 registrants. And oh yes, names like Olympic cyclist Tanya Dubnicoff, now an executive coach, synchronized skating coach Shelley Barnett, and others such as Manon Perron, Lee Barkell, and Skate Canada’s Coaching Development Committee members such as Laurene Collin-Knoblauch, Raoul Leblanc, Paul MacIntosh, Pascal Denis, Keegan Murphy, Mary-Liz Wiley, Megan Svistovski, and Chris Stokes will unleash their wisdom in workshops, too.

Have you booked your trip yet?