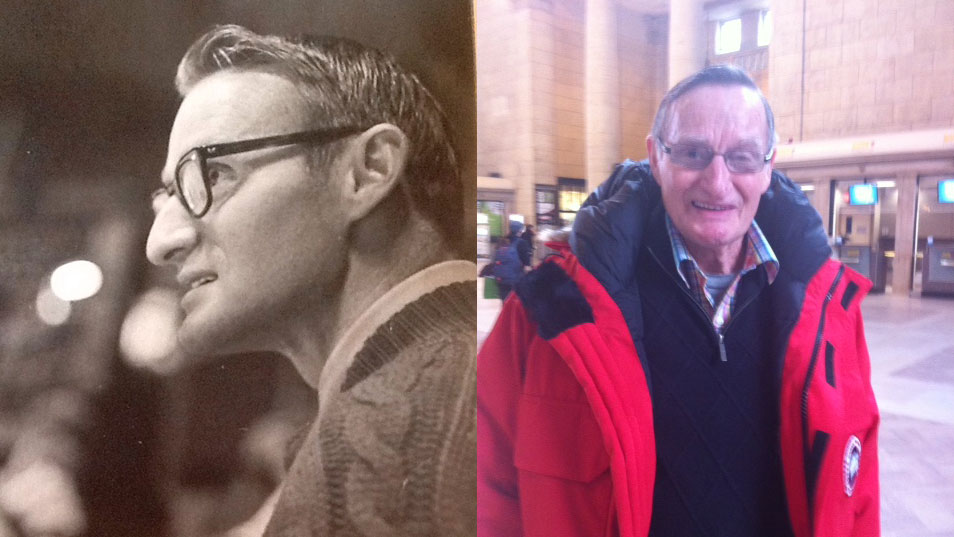

Still Coaching after 60 years!

It began as a way for a sickly child to get exercise but eventually turned into a life-long love affair with skating.

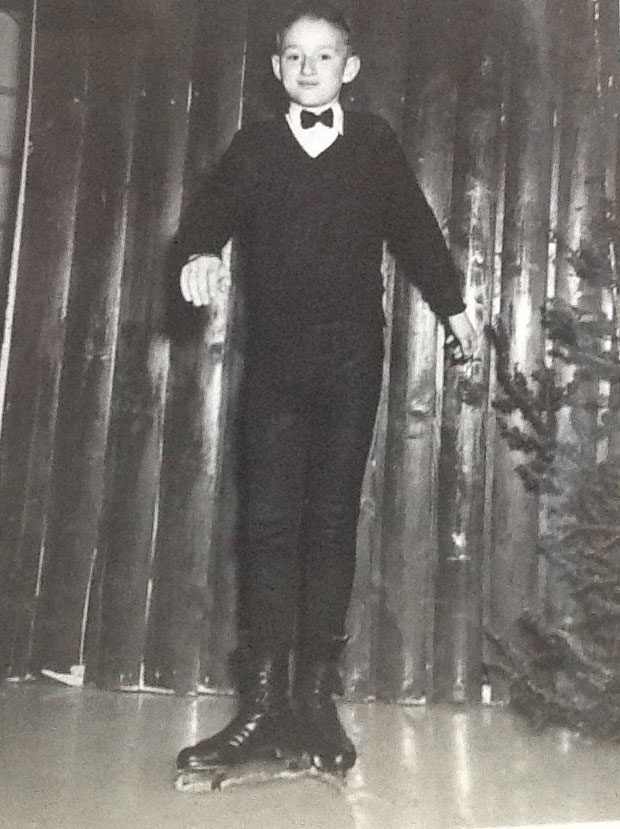

In the mid-1940s, Paul Tatton was 10 when he began skating at the North Bay Figure Skating Club. “I had been in bed with Pleurisy for over a year so naturally I wasn’t able to take part in active sports. Somehow I managed to pass my Preliminary Figure Test during my second season … and with that my love for skating was born.”

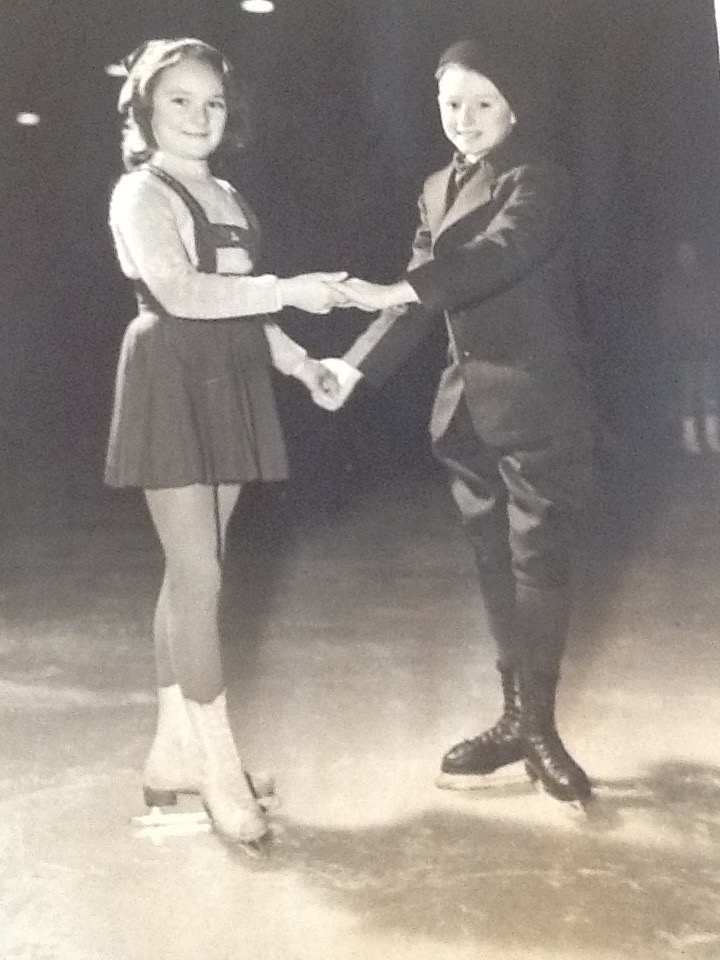

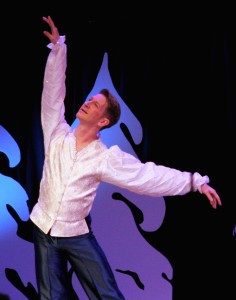

His efforts in his first ice show never indicated the kind of career that lay ahead. “While Sonya Henie was the star of the show, I was a frog along with two other young boys. We were skating on natural ice in an inch of slush and carried on so much that when we took off our costumes, we were green all over – the dye didn’t come off for a week!”

From the beginning, it was a family commitment, his parents volunteering for every job at the club, his mom eventually becoming a gold test judge. “After my second year’, says Paul, “my father drove me all the way to Toronto to get a half hour lesson with Coach Gerry Blair. At the end of the lesson he told me that I could be as good as I wanted — he could show me what to do but the rest was up to me.”

When Paul arrived back in North Bay he informed his parents that he had to live away from home to get skating time. His parents agreed and the next day drove him to Copper Cliff, west of Sudbury, got him a room, arranged for meals at a boarding house and enrolled him in the Copper Cliff Skating Club. “I was 13 years old”, tells Paul, “and got up at 4am every morning, walked to get breakfast, then to the rink and skated from 5am to 8.30, then off to school. I trained there with Mr. Blair on weekends and practiced on my own during the week.”

Paul admits that Gerry Blair took him under his wing and insured he had the things he needed to improve. “I had trouble with skating boots breaking down so Mr. Blair took me to see a friend of his, John Knebli. John made shoes for handicapped people. When shown my skates his immediate reply was ‘I CAN DO BETTER THAN THAT’! He took me back to his shop, measured my flat feet … and two weeks later I had the very first skating boots Mr. Knebli ever made. The rest is history.”

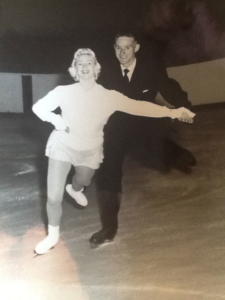

Under the guidance of Gerry Blair and later Sheldon Galbraith, Paul competed all the way to third place at Senior Canadians in 1954, finishing his free program despite experiencing an asthma attack part way through the performance. Returning home to skate in the official opening of North Bay Memorial Gardens, he knew his competitive career was at a turning point. Money was tight and with strict rules regarding amateur status, Paul felt he was almost forced to turn professional.

“Arena manager Morris Snyder asked me to run a Spring School for him. He thought I might have a good turnout and of course, loving a challenge, I wanted to see if I could do it. It turned out to be a success with all high tests passing.”

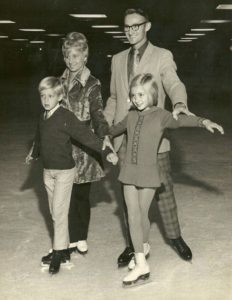

That started Paul on his life’s work. “The transition to coaching was easy … I’m a tremendous planner … and not just in skating.” Whether it was learning to fly and getting his certification after one month, being scouted by the Chicago Blackhawks of the NHL or receiving a scholarship to develop his high tenor operatic voice in Italy, whatever Paul set his sights on, he did with determination.

Thankfully Paul’s dedication to coaching skating won out.

He worked in the US, most notably in Hershey, Pennsylvania, at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio as the Director of Skating and finally back in Canada in 1976 after which he started his own school in Sundridge, Ontario. “Today I work for Riverside Skating Club, Windsor Skating Club and La Salle Skating Club in Western Ontario.”

Wherever Paul landed, he discovered it was the science of skating that kept him challenged, particularly during school figures. “I loved to see what happened if I turned my head one way, not the other. I still love doing skating research and then seeing the effects … it’s fascinating … I never get bored.”

He’s sad figures are gone. “Figures taught you to concentrate. Learning quality turns, body control and the tracing of a perfect edge was a real art form. It was the great divider; today it’s often just acrobatics.”

One of Paul’s former students, Jen Jackson, now a coaching colleague, recalls her early days under Paul’s tutelage. “I have known Paul since 1987 when I first moved to Windsor and was looking for a coach to help me finish my gold tests. I chose him because when I came into the rink to watch, even though he wasn’t teaching the best skater on the ice, he gave her a lesson filled with enthusiasm. I could see his passion for the sport … and he never watched the clock.”

Paul admits his priority has always been to instill confidence in the skaters he teaches. “I like to think that with each lesson I’ve accomplished something that will help them. You learn a lot about yourself in skating. You learn to face challenges that will benefit you for life. My coaches sure gave me confidence and for that I am grateful. Now it’s my job to pass that confidence on.”

In many ways, Jen has followed Paul’s teaching model. “When I began coaching, Paul was so generous and had me work with all his skaters. Now that he’s getting older, he’s stepping back, letting others take more leadership so he can work on specific areas with the skaters. He loves teaching turns and has become the Spin Doctor. The kids just love him. He always has a kind word or a story about the good old days and how each skater reminds him of someone wonderful he used to teach.”

Getting older has meant facing other challenges for Paul. Two years ago he had shoulder surgery and also broke his back, injuries which kept him off the ice for months.

As Jen says, it may have kept him out of the rink, but it did not curtail his enthusiasm. “When I would go to visit him, all he could talk about was how the kids were doing. He never complained about his situation and instead just kept telling me that he couldn’t wait to get back and hopefully by then he was still needed.”

Paul admits, “I’m proudest of the moments when I’ve helped kids do something they didn’t think they could do.”

Teaching from the boards, although Paul doesn’t put his skates on these days, he is as enthusiastic and involved as ever, this week attending the Annual General Meeting of Skate Canada Western Ontario and celebrating his 60th year of coaching.

Congratulations Paul!