Connaught Skating Club Offers Karen Magnussen A Helping Hand

One must never forget the sight of Karen Magnussen, dressed in snow white, flying aloft into a split jump that hovered in the air, then another in the opposite direction, free, dynamic, fierce.

One must never forget the sight of Karen Magnussen, dressed in snow white, flying aloft into a split jump that hovered in the air, then another in the opposite direction, free, dynamic, fierce.

The Vancouver skater had to fight for everything she won: five Canadian titles, an Olympic silver medal in 1972, a world title in 1973. Magnussen is the last Canadian woman to win a world championship gold medal, but nothing was easy for the skater with the pixie blond cut. Case in point? The battle she fought to come back from stress fractures in both legs that put her in a wheelchair on the eve of the 1969 world championships. Doctors told her that if she skated, she might not walk again.

“I don’t ever want to be told I can’t do something,” she said before being inducted into the Skate Canada Hall of Fame. She came back the next season with full force.

This was a typical Magnussen response to a hardship: she covered the 1969 world event for a newspaper, and turned the proceeds over to the Bursary Fund to help other skaters.

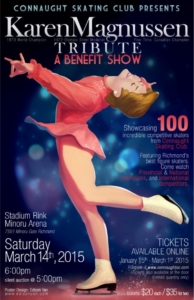

Now, once again, doctors are telling Magnussen that there is something she cannot do. It’s this last battle that is most formidable for Magnussen, so a tribute show to her, organized by the Connaught Skating Club on March 14 in Richmond, B.C. is “like a bright light in my life,” Magnussen said.

It’s a club with a heart that knows her story. On Nov. 28, 2011, after inhaling a blast of ammonia, a poisonous gas, as she prepared to teach young skaters at the North Shore Winter Club (where her parents had been one of the founding members), she has suffered catastrophic injury, lingering after-effects and endless battles with insurance companies that are loathe to pay up. She coughed for six months after the incident. Sleep was impossible. Magnussen can no longer work, can’t breathe properly, now suffers two autoimmune diseases linked to her medications (12 pills a day), has arthritis in her joints, and worst of all, can no longer even walk into an arena again. Any sort of fume could trigger a reaction. Before the accident, Magnussen was healthy. The ammonia had seared her lung tissue and her vocal cords, too.

Magnussen had hoped to coach into her seventies or eighties or even nineties, like Ellen Burka. Instead, with income halted, Magnussen and husband Tony Cella are now about to sell their home. It’s a devastating turn for a brilliant career. Connaught is trying to put that right, as much as they can with a fundraiser.

Magnussen didn’t think of herself first that fateful day. She scurried to get her students out of the rink first. There had been no warnings of a gas release.

Insurance? The Winter Club, so much a part of her life, did not reach out to help. Her administrative duties were handed off to someone else. Some insurance didn’t cover her because she wasn’t actually on the ice when the incident happenedA workman’s compensation deal dating back to 1917 allows payments to injured parties, but doesn’t allow the victims to sue the employer. The Canadian icon has fallen between all the cracks that could possibly exist for insurance.

“To have everything taken away from her is tragic,” said Ted Barton, Executive Director of the B.C. Section of Skate Canada. The section decided to take action, and when it discovered that the Connaught Club had once offered a charity fund-raising show, Barton approached them.

Connaught skating director Keegan Murphy, whose mother Eileen had been a close friend to Magnussen, jumped at the chance. “We always want to teach the younger generation that we can give something back to someone with our skating,” Murphy said. “We are honored to do such an important project.”

About 100 skaters will take part in the show, including Larkyn Austman, Mitchell Gordon, Garrett Gosselin and even a cast of 5-year-olds at their first ice show. Murphy, co-producer of the event, has tapped into some of Magnussen’s classics. One of the numbers? “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” – one of Magnussen’s exhibition numbers with Ice Capades, when she carried an umbrella. The little kids get to do that one.

Because of her issues with fumes, Magnussen will not be able to attend the show. Therefore the Connaught came up with a brilliant, thoughtful idea: to hold a meet-and-greet in one of the private rooms in the rink last week, where Magnussen could meet every single skater in the cast. Murphy has taken it upon himself to educate the youngsters about Magnussen. “It’s so important that the kids get to meet her,” he said.

Who knows this about Magnussen anymore? The three-year contract for $300,000 that she signed in 1973 to skate with Ice Capades was the largest it had ever offered a skater turning pro. “I liked Karen a lot,” said Lynn Nightingale, who skated against Magnussen. “I liked her sincerity. She was pretty down to earth. People who had her as a coach loved her. Life hasn’t been all that kind to her.”

What was it about Magnussen, aside from her medals that made her a skater to be remembered? She was a fierce competitor. Magnussen offered up wonderful skating moves that set her apart.

Some:

A change-direction, endless spiral, created by Magnussen and coach Linda Brauckman, in which Magnussen changes the position of a leg and her body to make a turn;

A layover camel spin, another Magnussen-Brauckmann invention;

An Ina Bauer into a double Axel combo

Splits going in both directions, followed by an Axel- butterfly-back sit spin;

A change of edge Ina Bauer into a flying sit spin;

A side layback spin that opened into a full flat layback spin.

Magnussen said she is “overwhelmed” by the helping hand offered by the Connaught club. “It really is very special. “

For years, Magnussen has distributed cheques to young skaters from her Foundation. One recipient of Magnussen money was Murphy, who said the attention paid by a former world champion meant the world to him.

Now, for a top-drawer skater who has given so much in her life, it’s time to give back. Not only can people buy tickets for the show, they can donate. Dick Button has already signed up.