Sheldon Galbraith’s funeral was anything but quiet and sombre.

Old friends by the numbers filed in and the chatter filled the room. The chatter became a din. It was like an old family reunion. Galbraith always had lots to say. So did his family and that includes folks who felt his big presence over the years.

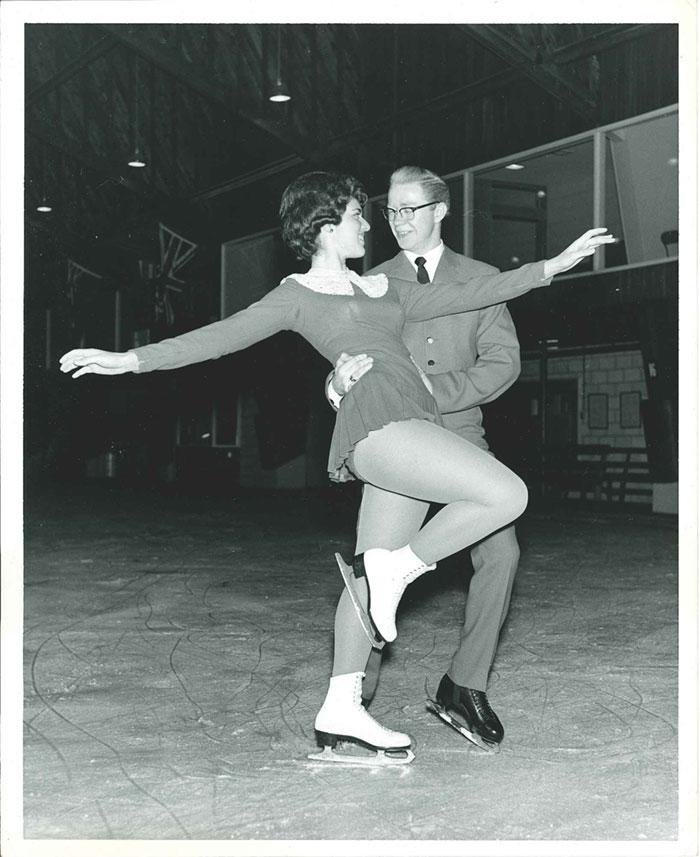

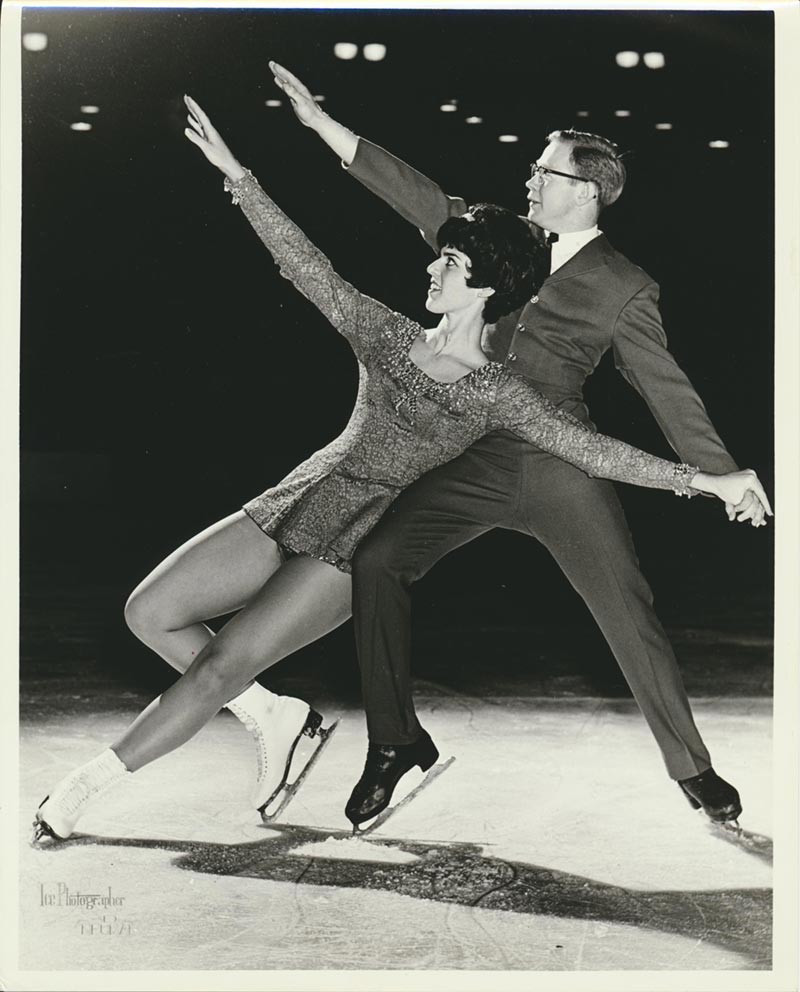

Galbraith was just short of 93 when he died on April 14, and it was clear from all the gibber, that the life he had lived was full and meaningful to many. He was a man who was a game-changer, ahead of his time, with a big personality that radiated gloriously through glossy black-and-white photos of him skating shadow pairs in his early Ice Follies days with brother Murray.

Photos lined the room of Galbraith’s life: an incredibly handsome photo of him in naval uniform; Galbraith toting an enormous golf bag, with an amused look thrown back over his shoulder; Galbraith going deer hunting, or perhaps it was for moose (the bigger the game, the better); Galbraith in his familiar coaching uniform – long baggy coat, big galoshes, cap with floppy ear flaps pulled over his head – as he leaned over to inspect a compulsory figure; Galbraith with family, wife of 69 years, Jeanne and their four daughters and one son; Galbraith receiving the Order of Canada.

Galbraith’s list of accomplishments is long: coach of Barbara Ann Scott, winner of the first Canadian Winter Olympic gold medal in 1948; coach of world champions in three of the four skating disciplines; coach of Olympic champs Barbara Wagner and Bob Paul, the first Canadian pair to win this gold; two-time world champions Frances Dafoe and Norris Bowden, who also took Olympic silver; coach of 1962 world champion Donald Jackson, who became the first skater to land a triple Lutz in competition, coach of Vern Taylor, credited with the first triple Axel.

He also earned a string of awards: he was the first figure skating coach to be inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame (1980), and he’s also a member of the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame (1990), the Canadian Figure Skating Hall of Fame (1991), the World Museum Hall of Fame in the United States (1996) and the Professional Skating Hall of Fame (2003). Galbraith, the first president of the Professional Skating Association in Canada, also received the Order of Canada and the Order of Ontario.

But reading between all of those lines is even more astonishing. Brian Foley, the Pied Piper of Canadian dance who also choreographed for Dorothy Hamill, Robin Cousins, John Curry and Toller Cranston, said he first set foot at the Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club in 1966, when he met Galbraith, then the head coach.

“I’ll never forget that first introduction with Sheldon,” Foley said. “He was, in his way, very polite in chastising me, that I was standing and teaching in his space.”

In a far corner of that space, Foley saw the many teaching tools Galbraith used to bring out the best in his skaters: “a homemade flying contraption,” Foley said. “Trampolines with crash mats. A few wooden poles. Some climbing apparatus and other paraphernalia that reminded me of an early Cirque du Soleil.”

And who could ever forget the video room? “I want to assure everybody that nobody was invited or allowed into that room,” Foley said. Well, international judge Jane Garden did. Galbraith showed her videos, taught her to see errors, made her a better judge. Later, he advocated for judges to pass on what they learned at skating events. Not only did he teach skaters. He taught judges.

Galbraith spent his life researching and developing his own philosophies, adapting his training as a flight instructor to figure skating. He made it all a science, but intuition worked too. Technique in figures, jumps and spins was all-important. He taught the science of momentum and balance and centre, which are elements that you need to do quality spins, Foley said. He researched the physical transfer of weight from edge to edge, carrying the weight appropriately over the ball of the foot. He measured the amount of velocity required in order to skate forward and backward with great flow.

If there is anybody who carries the Galbraith torch of technique, it is Gary Beacom, the master of the skate blade. “I am grateful that my most influential coach plumbed the depths of technique with such enlightenment and a sense of adventure,” Beacom said. “I credit my skating proficiency and capacity for innovation to decades of training the Galbraithian relationship of speed, curve, lean and rotation. Sheldon Galbraith advocated continuous harmonious motion using momentum and rhythm for both technical and artistic advantage.”

Beacom says he had Galbraith to thank for reviving the cross-foot spin as a compulsory program element during the mid-1970s. The cross-foot spin became Beacom’s signature move.

Casey Kelly, now an international judge, began to take lessons from Galbraith when her family moved back to Canada in 1973. She remembers his fairness and sense of equality. Cranston had a habit of drifting over the lines of the space allotted to him for training figures. He was working toward a world championship: Kelly was working on her third test. She would politely step aside for Cranston.

However, Galbraith told her: “Don’t you dare stop. You deserve to be here just as much as he does.” Kelly smacked into Cranston three times, before he finally moved back into his own space. “That was something I never forgot,” she said.

Donald Jackson also discovered Galbraith’s sense of fair play before he even began to work with him. Jackson had been training with Pierre Brunet in the United States, but Galbraith, the Canadian team coach, took over watch on Jackson during the 1960 Olympics when Brunet was too busy with other skaters.

Galbraith was the official coach of Wendy Griner at the time and the question became: who would take to the practice patch first? “It was always better to skate second, because the ice would be a little bit softer and more like the ice you were skating on when you skate in front of the judges,” Jackson said.

Jackson was astonished when Galbraith flipped a coin to determine who he would coach first. He could easily have saved the best patch for his own student. “That was just the type of man he was,” Jackson said. “Fair. Honest. It was what I really appreciated.” The next season, Jackson moved into Galbraith’s fold.

Galbraith changed the technique on all of Jackson’s jumps, laboriously. Then one day, he asked Jackson to do a double flip, which Jackson could do with his arms folded. But Galbraith told him to relax into a backspin position as he went up. “No problem,” thought Jackson, who promptly landed on his toes and fell, hard. Galbraith glided over and said: “I saw what I wanted to see. Don’t do it again.”

It was too late for Jackson to change that technique on a flip. But now, everybody does jumps with backspin technique. “Every time I see the skaters doing triples and quads, I think of what Mr. Galbraith developed for skating,” Jackson said. “And I think of my bruise, too. I guess I was the guinea pig.”

And yes, he was Mr. Galbraith to everybody. Hardly anybody ever called him Sheldon. Barbara Wagner said she called him Mr. Galbraith even as she became an adult. Kelly said her mother, Andra, never called him Sheldon, even though they’d sit next to each other at Hall of Fame functions, because of her husband, hockey great Red Kelly.

“He was a very special man who was way ahead of his time,” Wagner said.